In the first thirty years of the twentieth century, a new art form took the world by storm. Movies captivated the masses in a way nothing else ever had, and our love affair with movies has continued to the present day.

Early moviegoers were treated to a grand spectacle for their nickel. Theaters were large and opulent, especially in the bigger cities. While the massive, ornately decorated downtown theater quickly became known as the movie palace, and the cathedral of the motion picture, virtually every neighborhood and small town boasted at least one “Bijou.” Theaters offered and escape from the trouble of the world. Within their dark, cavernous auditoria, one was pampered by a huge uniformed staff of ersatz servants. The movie might be a part of a larger show which included musical numbers and stage acts. Often that show would include a performance on a giant pipe organ which was installed in the auditorium.

The story of the theater organ is the story of the movie palace which housed it. Music was required for the live song and dance performances that were incorporated with a movie into a larger spectacle, and the movies were silent and needed live renditions of the soundtrack and sound effects. Theaters employed staff musicians, sometimes entire orchestras to provide live music for the stage acts. In smaller, less affluent settings, a piano would serve as the sole musical accompaniment to this live entertainment.

The impresarios who brought these nightly extravaganzas to an eager public were searching for something new and different. What better way to contribute to the image of theater as a cathedral of the motion picture than the peal of a mighty pipe organ? An added incentive was the savings afforded by having to pay only one musician, who produce sounds approaching those of an orchestra of dozens of players while seated a single organ console.

The first pipe organs to appear in theaters were little more than transplanted church organs. While they looked and sounded impressive, they were ill-suited to the performance of the popular music of the day. The instrument quickly began to evolve into an entirely different type of instrument, one which far better suited its intended purpose. Many of the innovations which led to the perfection of the theater organ were the work of one man, a brilliant English inventor named Robert Hope-Jones.

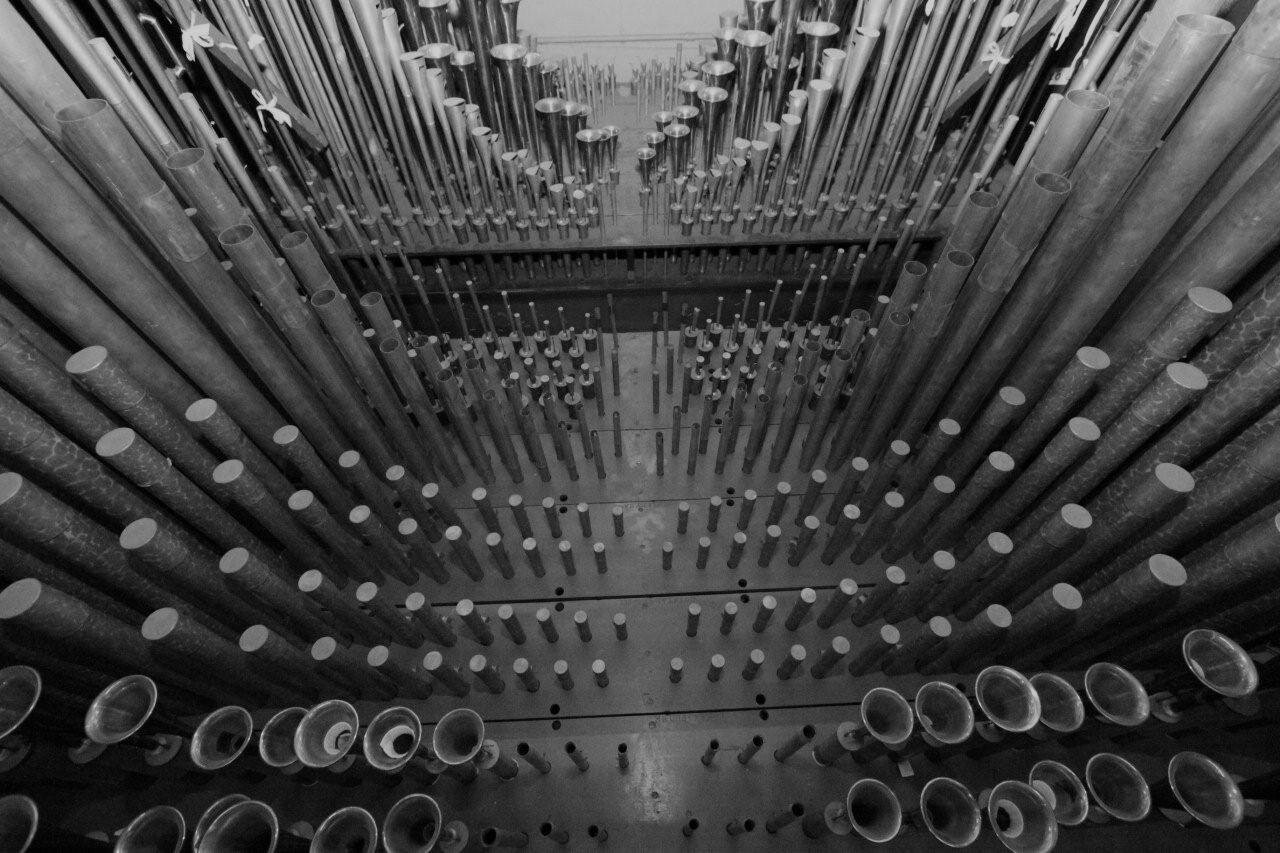

The Wurlitzer factory. Photo taken in 1996 by Jeff Cushing.

Hope-Jones developed many of his innovative ideas regarding organ design in his native England, but it was not until his arrival in America and his fruitful collaboration with Rudolph Wurlitzer and the Wurlitzer company of North Tonawanda, NY that many of his ideas were realized. The product of that collaboration was called “The Wurlitzer-Hope-Jones Unit Orchestra,” and although it quickly became known as the “Mighty Wurlitzer,” its official name better reflected its nature as the instrument had truly become a one-man substitute for the orchestra.

Unfortunately, after some major disagreements with the Wurlitzer management, Robert Hope-Jones took his own life in 1914 – but not before profoundly influencing the development of the theater organ. The Wurlitzer company continued to flourish, becoming the largest manufacturer of theater pipe organs in the world.

In the early twentieth century, several thousand theater pipe organs were installed across America. The term “theater organ” originally referred to any organ installed in a theater, but as the instrument evolved, the term began to refer to this specific type of instrument; theater organs were installed and used in sports arenas, civic auditoria, and even churches!

History of the Senate Theater & the Detroit Theater Organ Society

The Past

The Fisher Theater’s Mighty Wurlitzer Organ finds a new home at the Senate Theater

In 1927 the Fisher family asked architect Albert Kahn to design a multi-purpose building including a theater. Fred Fisher, announcing the plans in January of 1927 commented, “Our aim is to create the outstanding building in the city and express in this highest character the Fisher’s appreciation of what our adopted city means to us.” Located at Grand Boulevard and 2nd Avenue, the 28-story tower was topped with gilded roof panels. The Detroit Times wrote “The tower will be to Detroit what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris.” Decorated with a Mayan motif and including a lobby complete with a pond, goldfish, turtles, and five talking macaws; the gilded walls dazzled visitors who attended movies, concerts, and stage shows.

The organ, a 4 manual 34 rank Wurlitzer, was installed in the theater as a memorial to the parents of the seven Fisher brothers who enjoyed classical organ and gospel hymns. It was the eighth largest Wurlitzer ever constructed, and the contains stops not usually found on theater organs which enables the music of Bach to be performed with magnificent glory as well as the music of Gershwin.

“Talkies,” or movies with recorded audio tracks, came in soon after the dedication in 1928. The theater continued to present films through the years, but the usage of the organ became far less frequent. In 1961, the Fisher Theater was to be remodeled, and the organ was sold to George Orbits, a local organ buff.

Orbits and several friends created The Detroit Theater Organ Club (DTOC) in 1961 and leased the old Iris Theater on East Grand Boulevard where the organ was installed. Many great concerts were performed there by the top performing artists of the country. The Iris Theater was soon outgrown, causing Orbits and the DTOC to search for a new venue. The derelict Senate Theater was found in 1962 and club members spent several thousand hours over two years restoring the building.

The Present

The Senate Theater, designed by architect Christian Brandt, originally opened October 7, 1926. Mainly a movie theater, it also presented some young comedians and entertainers on their way to later stardom, including Danny Thomas. The theater closed in 1955 after a short period of showing fringe movies and being used for church services. Following two years of renovation and restoration, the theater was returned to its landmark glory on Michigan Avenue. The dedicatory concert on April 11, 1964 featured the celebrated New York organist, Ashley Miller. There have since been over 700 concerts performed.

In 1989 the DTOC was renamed the Detroit Theater Organ Society (DTOS), an all-volunteer non-profit organization. The organ has now been playing longer in the Senate Theater than in its original home in the Fisher Theater. DTOS continues to make the Senate Theater its home, with a mission to preserve the art of theater pipe organ music by maintaining and showcasing the Mighty Wurlitzer at concerts, film screenings and events hosted at the theater.

How Do Theater Organs Work?

At the Senate Theater, we see the organ console on the stage, and we hear the music emanating from various locations around the auditorium. But what is an organ? What are its parts? And how does it all work?

Console

The organ console is the large key-desk at which the organist controls and plays the organ. Most commonly, it has two or three manuals (keyboards), but some have as many as six! The manuals are surrounded by a semicircle of stop tabs. There is also a large foot pedal board and many other buttons and pedals that control the swell shutters, sound effects, and mechanics of the instrument.

Blower

A 25-horsepower turbine provides the pressurized air that blows through the pipes. It also provides air to operate the mechanical devices which play other instruments (traps). Pressurized air is also used for other mechanical tasks, such as the operation of the swell shutters and the registration pistons that automatically change many stops at the press of a button.

Windchest

This is a wooden reservoir that contains pressurized air from the blower. Valves in the windchest are opened and closed remotely by the relay to cause the correct pipes to sound when the organist depresses the keys.

Relay

The “brains” of the organ are in the relay. Electrical signals generated whenever keys are pressed, or stops are changed directs corresponding pipes and traps to instantly sound. Various components of theater pipe organ are often at a considerable distance from one another and must be connected by miles of electrical wiring.

Pipes

A set of pipes that produces the same distinctive sound is known as a rank of pipes. Most ranks contain 61 or 73 pipes. Small theater pipe organs could have as few as three or four ranks of pipes, and the largest instruments had over fifty ranks. In actual numbers of pipes, a small instrument might have 100-300 pipes, while the largest instruments contained up to 30,000. The highest sounding pipes are smaller than a pencil. The lowest bass pipes in large instruments are bout 32 feet in length, and wide enough to allow a person to stand inside a pipe.

Traps & Toy Counter

Authentic percussion instruments such as piano, xylophone, orchestra bells, and drums are in the pipe chambers. These instruments are played from the keys of the organ and played be mechanisms powered by the same pressurized air used to make the pipes sound. Separate beaters or hammers are located above each metal or wooden bar on the pitched percussion instruments. Pneumatic actions also control the hammers that strike the strings of a real piano in the pipe chamber. Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, and other percussion instruments are activated in the same manner. Sound effects such as siren, automobile horn, and train whistle, are all sounded from the organ console.